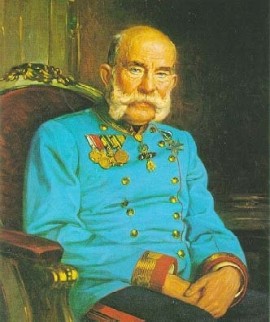

Francis Joseph I (1848-1916)

Francis Joseph, German Franz Joseph (born August 18, 1830, Schloss Schönbrunn, near Vienna—died November 21, 1916, Schloss Schönbrunn), emperor of Austria (1848–1916) and king of Hungary (1867–1916), who divided his empire into the Dual Monarchy, in which Austria and Hungary coexisted as equal partners. In 1879 he formed an alliance with Prussian-led Germany, and in 1914 his ultimatum to Serbia led Austria and Germany into World War I.

Francis Joseph was the eldest son of Archduke Francis Charles and Sophia, daughter of King Maximilian I of Bavaria. As his uncle Emperor Ferdinand (I) was childless, Francis Joseph was educated as his heir-presumptive. In the spring of 1848 he served with the Austrian forces in Italy, where Lombardy-Venetia, supported by King Charles Albert of Sardinia, had rebelled against Austrian rule. When revolution spread to the capitals of the Austrian Empire, Francis Joseph was proclaimed emperor at Olmütz (Olomouc) on December 2, 1848, after the abdication of Ferdinand—the rights of his father, the archduke, to the throne having been passed over. Hopes of a revival of monarchist sentiments were raised by his radiant, youthful appearance.

Of all his mentors, the old chancellor Klemens, Fürst (prince) von Metternich, probably exerted the most lasting influence on Francis Joseph. A more profound influence, however, was that of his wife, the duchess Elizabeth of Bavaria. He married her in 1854 and remained deeply attached to her throughout a stormy marriage.

During the first 10 years of his reign, the era of so-called neo-absolutism, the emperor—aided by such outstanding advisers as Felix, prince zu Schwarzenberg (until 1852), Leo, Graf (count) von Thun und Hohenstein, and Alexander, Freiherr (baron) von Bach—inaugurated a very personal regime by taking a hand both in the formulation of foreign policy and in the strategic decisions of the time. Together with Schwarzenberg, who had become prime minister and foreign minister in 1848, Francis Joseph set out to set his empire in order.

In external affairs Schwarzenberg achieved a powerful position for Austria; in particular, with the Punctation of Olmütz (November 1850), in which Prussia acknowledged Austria’s predominance in Germany. In home affairs, however, Schwarzenberg’s harsh rule and the formation of an intolerant police apparatus evoked a latent mood of rebellion. This mood became more threatening after 1851, when the government withdrew the promise of a constitution, given in 1849 under the pressure of the revolutionary troubles. That retraction had long aftereffects and led to the liberals’ permanent distrust of Francis Joseph’s rule. In 1853 there was an attempt on the emperor’s life in Vienna and in a riot in Milan.

After Schwarzenberg’s death (1852), Francis Joseph decided not to replace him as prime minister and took a greater part in politics himself. Austria’s mistaken policy during the Crimean War originated largely with the emperor, torn between gratitude to Russia for its help in quelling a rebellion in Hungary in 1849 and the advantage the monarchy might derive from siding with Great Britain and France. The mobilization of a part of the Austrian Army in Galicia on the borders of Russia in retrospect turned out to have been a grave error. It gained no friends for Austria among the Western powers but lost considerable goodwill that Tsar Nicholas I had earlier harboured for Francis Joseph.

At home, neo-absolutism resulted in a civil service staffed by highly competent experts who tried to meet the emperor’s high standards but whose limitations nevertheless became increasingly obvious in 1859–60 as they attempted to deal with the empire’s complex financial problems. Army expenditures had to be curtailed in 1859, when a series of ill-fated wars began that seriously shook Austria’s military reputation. Moreover, the police regime proved to be impracticable in the long run. Thus the government made critical military decisions against a background of many unresolved problems in finances and home affairs. For many of these decisions, especially the unfortunate outcome of the war of 1859 against the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Empire of France, the emperor was responsible.

After provoking Austria into war, Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour, the prime minister of Sardinia, planned to use the French Army to oust Austria from Italy. When the imperial commander in chief proved incapable, Francis Joseph himself took over the supreme command, but he could not prevent the defeat of Solferino (June 24, 1859). Dismayed by Prussia’s demand that, as a condition of its intervention on the emperor’s side, the Austrian Army be placed under Prussian command, Francis Joseph hastily concluded the Peace of Villafranca in July 1859, under which Lombardy was ceded to Sardinia. Unreconciled to this settlement, Francis Joseph adopted a foreign policy that prepared the way for a passage at arms with Italy and Prussia, by which he hoped to regain for Austria its former position in Germany and Italy, as it had been established by Metternich in 1814–15.

The mood of crisis after the defeat of 1859 caused Francis Joseph to pay renewed attention to the constitutional question. A period of experiments—alternating between federalistic and centralistic charters—kept the country in a permanent state of crisis until 1867. The congress of princes at Frankfurt in 1863, for which the reigning heads of all German states assembled with the sole exception of the king of Prussia, was a high point in Francis Joseph’s life. Yet the absence of the Prussian king demonstrated that Prussia no longer regarded Austria as the leading German power.

Francis Joseph had vainly tried to postpone the decision for predominance in Germany by entering into a comradeship-in-arms with Prussia in a war against Denmark in 1864. After their victory, squabbles arose between them, and war with Prussia became inevitable. The conclusion of an alliance between Italy and Prussia pointed up the dangerous possibility that both foreign-policy problems might have to be faced at the same time, yet Francis Joseph failed in his attempt to avoid an armed conflict at least with Italy. In June 1866 Austria concluded a possibly unique agreement with Napoleon III of France that stipulated that Austrian-held Venetia was to be given to the Kingdom of Sardinia regardless of the outcome of the impending war with Prussia. As the emperor considered it incompatible with the army’s honour to cede a province without fighting, war with Italy broke out despite the agreement. In later years, Francis Joseph characterized his policy of yielding territory with one hand while fighting for it with the other as honest but stupid, whereas the chancellor Friedrich Ferdinand, Graf (count) von Beust, called the agreement the most shocking document that he had ever seen. Although its defeat in the war with Prussia that the Prussian prime minister Otto von Bismarck had forced on the unprepared monarchy caused Austria no territorial loss in the north, it nevertheless sealed Austria’s expulsion from Germany. The victories gained by the Austrian Army in the south, moreover, could not prevent the loss of Venetia, so that Austria found itself expelled from Italy as well.

The appointment of the Saxon premier, Beust, as Austrian prime minister in 1867 shows that initially Francis Joseph was once again unwilling to accept the decision. Beust’s cherished project of an Austrian-French-Italian alliance against Prussia did not materialize, however, and in 1870 the attitude of the Hungarian prime minister, Gyula, Gróf (count) Andrássy, coupled with the rapid military successes of Prussia, prevented Austria from joining in the Franco-German War at the side of France. Andrássy, appointed imperial foreign minister after Beust’s dismissal in 1871, inaugurated the policy of close collaboration with Germany that later became the cornerstone of Francis Joseph’s foreign policy.

The failure to achieve a federalist solution satisfactory to all nationalities had exacerbated relations among them. In 1867 it had become obvious that a compromise had to be made with the restive Hungarians. The newly appointed prime minister Beust was, however, insufficiently informed about conditions in the various parts of the Austrian Empire. The result was the kaiserliche und königliche Doppelmonarchie, the “imperial and royal Dual Monarchy” in which an Austrian and a Hungarian half coexisted in equal partnership. The compromise, however, gave the Hungarians considerable leverage to extend their influence. The losers were the Slav peoples, for the Bohemians (Czechs) and Poles did not share in the privileged position of the German Austrians in the Austrian, or western, half of the empire, while the Croats, Slovaks, and South Slavs had none of the prerogatives enjoyed by the Hungarians in the Hungarian, or eastern, half. With this preferred treatment, which Francis Joseph recognized as such, the multinational state had violated its inner law of the basic equality of all national groups. The individual crownland’s relationship to the emperor, which in each case had been the result of a long historical evolution, was now replaced by the submission of the various nationalities to German-Austrian or Hungarian overlordship. Internal restlessness thus continued unabated. A final attempt at reform by which the Slavic languages were to be given equal status with Hungarian and German was vetoed by Francis Joseph under pressure from the German-Austrian nationalists. But, under the influence of the Viennese sociologist Albert Schäffle, the emperor, who on the whole had little use for party politicians and their influence on public life, seems to have followed the continuing process of democratization in his empire with some sympathy.

The question of recognition and restoration of ancient Czech rights hobbled Austro-Hungarian foreign policy and poisoned domestic politics. Even more of a handicap was the problem of the South Slavs. From 1867 on, the Hungarian-ruled Croatians found themselves subjected to a continuing process of Magyarization. Hungarian domination eventually turned Serbia, inhabited by fellow Slavs, into the Dual Monarchy’s mortal enemy.

Francis Joseph, who wholeheartedly supported the Ausgleich (the Hungarian Compromise) as the constitution of the Dual Monarchy, failed to grasp the negative aspects of that highly complex document. Interested primarily in questions of foreign policy and military leadership, he paid too little attention to domestic affairs to understand the nationalities problem in all its gravity. In particular, he failed to see the connection between Austro-Hungarian internal affairs and their effect on the monarchy’s relationship with Russia and on the political situation in the Balkans.

Although Francis Joseph always considered foreign policy his own specialty, he was in effect guided by the ablest among his foreign ministers: Andrássy, Gusztav Siegmund, Graf (count) Kálnoky von Köröspatak, and Alois, Graf (count) Lexa von Aehrenthal. Andrássy not only launched the alliance with Germany in 1879, but, by carrying out the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which Francis Joseph had advocated and the Congress of Berlin (1878) had sanctioned, he also gained the first great foreign-policy success of the empire in the Balkans. Francis Joseph defended the German alliance against all opposition. He was considerably more reserved toward Italy, which had joined Germany and Austria in the Triple Alliance in 1882, and Romania, with which Austria-Hungary had concluded a secret treaty in 1883; in fact, his reticence contributed to the eventual alienation of both of those allies.

The style of Francis Joseph’s foreign policy was dynastic and personal. Just as he had contributed decisively to the creation of the League of the Three Emperors (Dreikaiserbund) by appearing in Berlin in 1873 by the side of Tsar Alexander II, he endeavoured also on later occasions to forestall potential conflicts with Russia through personal contacts, without realizing the fundamental nature of the antagonism between the two countries. On a visit to St. Petersburg in 1897 and again after Tsar Nicholas II’s visit in 1903, he tried to delimit Austrian and Russian interests in the Balkans—a policy that was rashly jeopardized by Aehrenthal during the crisis leading to the annexation of occupied Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908. By then, however, the days were long past when foreign policy was a matter of friendships between sovereigns; conflicts of interest, or for that matter pan-Slav propaganda, could no longer be neutralized on the dynastic level. Also, the emperor found it increasingly difficult to get along with his fellow sovereigns, many of them relatives, of the younger generation. Yet he seems to have appreciated the energetic, dashing, and optimistic manner of William II of Germany.

In the period 1908–14 Francis Joseph held fast to his peace policy in the face of warnings by the chief of the general staff, Franz, Graf (count) Conrad von Hötzendorf, who repeatedly advocated a preventive war against Serbia or Italy. Yet, without having fully thought out the consequences, he let himself in July 1914 be persuaded by Leopold, Graf (count) von Berchtold, the foreign minister, to issue the intransigent ultimatum to Serbia that led to World War I.

Although he had been raised to be a soldier and wore a uniform all his life, Francis Joseph was no more a strategist than he was a statesman. He made up for this deficiency by the careful study of documents, by an extraordinarily retentive memory, and by being a shrewd judge of character. Invariably well informed and familiar with the reports of his envoys, he was to his civil servants an unequaled model of exactitude, devotion to duty, and justice. In his time Austria-Hungary was credited with having a civil administration that was as efficient as any in Europe. Having reserved for himself the control of foreign policy and of all matters bearing on the army, he stated repeatedly that this foreign policy was his own and that any criticism of it was in reality directed at himself. While loyal to his ministers, he refused to grant them any influence beyond the limits of their respective offices; once dismissed, a minister was no longer consulted on official business. This attitude, which many considered to be both ungrateful and ungracious, sprang in part from a punctiliousness that was hard to penetrate and rendered him incapable of true friendship. In the early decades of his reign, his correct but unapproachable bearing caused Francis Joseph to be respected but not really popular. Toward the end of his life, however, he became a universally revered man, a personality that for all its defects and insufficiencies held together the rotting structure of the multinational state.

Although a gentleman of irresistible charm in personal contact, Francis Joseph was greatly feared as the head of his house. His attitude toward his family was determined primarily by dynastic considerations. His own marriage had been a love match, and he remained devoted to his wife even after the marriage had been wrecked by her eccentricities. Her assassination, in Geneva on September 10, 1898, saddened him profoundly. The tragedy of the heir apparent, the archduke Rudolf, who dramatically shot himself in a suicide love pact with a 17-year-old baroness at Mayerling on January 30, 1889, was assuredly rooted in Rudolf’s unstable character. Yet the emperor had contributed to his only son Rudolf’s instability by giving him an unsuitable education, forcing him to marry Princess Stephanie of Belgium, and dealing with him in an altogether cold and uncomprehending manner. He treated his daughter-in-law with unforgiving harshness after her second, morganatic marriage, believing that family members who married beneath their station had committed a crime against the dynasty. Furthermore, Francis Joseph never became reconciled to the morganatic union of the next heir presumptive, Archduke Francis Ferdinand. His statements on receiving the report of the archducal couple’s murder at Sarajevo, on June 28, 1914, show that he looked upon their fate as a token of divine retribution. These tragedies, which became public knowledge, were underlined by an unending series of sometimes heated family disputes in the course of which Francis Joseph forced the members of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine to conform to his own notion of an archduke’s dignity and position. Yet this man who became ever lonelier as time went on could be a generous and amiable family father to his daughters and those members of the house who bowed to his wishes.

The only member of the immediate family with whom he had a closer relationship was his youngest brother, the archduke Louis Victor. While he was no more than correct in his attitude toward his brother, the talented and ambitious archduke Maximilian, he bears no blame for the tragedy that ended Maximilian’s brief interlude as emperor of Mexico.

Having overcome the threat to its survival in 1848–49, Austria passed through a long metamorphosis with many ups and downs in the 68 years that Francis Joseph occupied the throne. His many mistakes were balanced by splendid achievements. The social legislation enacted by the prime minister Eduard, Graf (count) von Taaffe, during the 1880s, the new penal code of 1852, the trade regulations of 1859, and the commercial code of 1862 are all examples of a civil administration that was highly regarded throughout Europe. Those achievements bore the stamp of the emperor’s own silent devotion to duty.